Two Things Together

It’s May and it’s just spring here, which is the right time to write to you about a particular folk song. It’s a May Day song, really, the Old May Day, a song for long days and the beginning of summer.

It’s a song about getting up before everyone else and feeling full of yourself over it. It’s a song about a warm morning.

It also shares a verse with As You Like It, which is real weird. It’s weird enough to talk about.

The song is Hal-an-Tow. (This links to a youtube video with a timestamp; it may not get to the right place on mobile. The time I mean to link you to is 13 minutes and 12 seconds.)

Here’s the thing about folk musicians:

When you get folk musicians together, they do the following things. They will sing, they will have a drink, and then they will talk. And because they are amateur scholars of very specific histories, they will talk about music. About the song, you know the one, the one that goes like, “something something sun… something… she rises”?

Here’s something they talk about: how did this verse get in that song? Where did it come from? Is it authentic?

So many folk songs are temporally indistinct – the kind of songs where people just started singing them, building them from scraps of literature and sayings and whatever words fit a good melody. Maybe it’s got a theme lifted from a hymnal. Maybe the hymn itself was lifted from a drinking song. These are small, quiet mysteries.

(There are some good stories here, like how a fragment of this very song ended up sung by children of Cabool, Missouri, in the 1940s, but that’s not what this letter is about.)

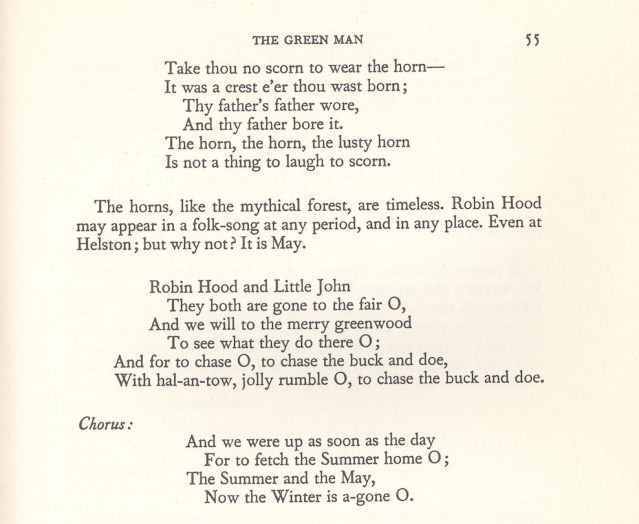

Hal-an-Tow has a very specific mystery. What is the deal with the Shakespeare?

The whole song is from Cornwall, and is probably from the early 1600s. It has a place and a ritual. It’s a song that is, mostly, well-situated in time.

Shakespeare lived half a decade earlier, halfway across England.

Here’s what happened.

Someone printed that song in a book and prefaced it with a quotation of Shakespeare. Not with any intent, really, it was just two things about spring in the same place.

It kind of fit, lyrically, if you added a word midway and dropped the final couplet. Now it is inextricably part of the tradition of that song.

(In Helston they sing it the good old way, I hear, and you can find a very, very insistent correction of the history I’ve just described on the Wikipedia page.)

Two things together will often become one thing. Like trees do, if you plant them too close together. Their trunks and branches will inosculate and they will be, in time, one tree.

(You could use this to grow a hedge or a nice topiary.)

I’m telling you about this because it happens with computers. It happens all the time. Code is all made of the same kind of stuff, broadly speaking, and if you put one bit in contact with another it will fuse, quick as contact welding.

(Contact welding is a thing that happens in space, when two pieces of steel lose the oxidation that happens in earth’s atmosphere. If two pieces of steel should happen to touch, they are now one piece of steel; they’re the same material, how could you tell what was part of the original pieces? As far as I am concerned this is sympathetic magic.)

If you’ve spent time with computers, you’ve experienced this yourself – things close to each other have a way of blending themselves together, adapting themselves to each others’ use no matter how hard you try to keep them apart.

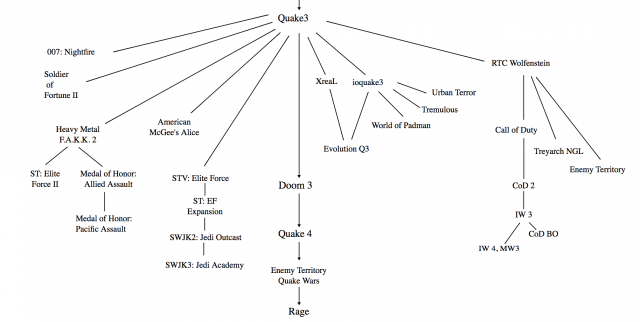

But it’s not just separation of concerns that I am concerned with. There are the Katamari Damacy programs that have rolled up too many things. There’s the kind of code that gets included by accident because you’ve copypasted and you don’t even know it’s there. There’s the kind you wrote yourself and included in every program and it was very good at the time, but then you learned about mutexes and it didn’t seem quite so perfect anymore (this is a real thing that happened in BSD Unix circa 1995. Maybe in a future letter).

There is code that you’ve copied in intentionally from elsewhere, but you don’t know quite what it does.

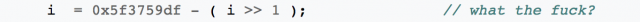

A piece of video game code famously included the preceding piece of code–the “fast inverse square root”. It’s famous enough that it–nine lines all-has its own Wikipedia page. When determining how bright a surface should appear to a viewer, you’ll need to compute a vector normal, and for that you’ll need to divide a number by its square root. This code does that very, very quickly.

For years, it was not widely known how or why this worked, but it did the right thing very quickly, so there it was. It stuck around on Usenet for years, until folks realized that their computer processors had in the mean time developed an instruction to compute the inverse square root quicker than this code could.

This example is famous enough, and magical enough, that we know where it came from, and we know, roughly, where it went.

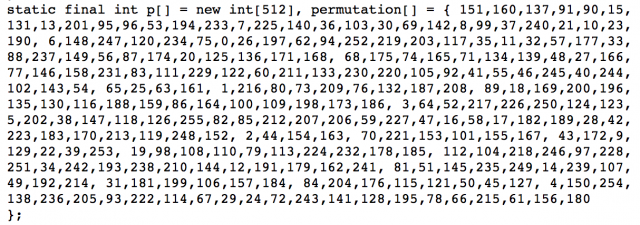

But these kind of fragments are all over. Ken Perlin’s original table of values for Perlin noise must exist in ten thousand programs by now.

When you read a computer program and see something unfamiliar, or something unnecessary, it may be one of these. I hope you notice these things and take the time to wonder at them. I hope you wonder about their times and places and rituals.

This has been About Computers. Thank you so much for reading.