Looking at Computers

First: my wholehearted thank you to Luna. I could not have written this without her help. Go follow her blog for good writing about computers.

It turns out you can learn a lot from computers just by looking at them.

This involves a clever and litigious company, trademark law, a microscope, nitric acid, and one very dedicated materials science student.

Here’s the thing about gameboys:

When a Nintendo Game Boy boots up, the Nintendo® logo scrolls down the screen. There’s a little ba-ding! when it hits center screen. (If you’ve held a gameboy, the sound it makes is playing in your head right now. If not, you can listen to it here, to get in the mood.)

You’ve put a game in your gameboy, so you then go on and play the game. But what I want to talk about first is the scroll and the sound and what happens right, right after.

The routine that does the scroll and the ba-ding! is encoded in the gameboy’s ROM, its read-only memory. There’s one dedicated little chip full of Z80 instructions inside the gameboy that does that. One chip, just for the scroll and the sound! After that small fanfare, the ROM will jump to the actual game you’ve put in.

So what’s this for?

That chip—that bootrom—has a copy of the Nintendo logo, but it doesn’t draw it on screen.

Instead, it looks at a particular memory location in the game cartridge (say, Pokémon Red) and draws whatever data is there as the logo. The little pixely ®, by the way, lives on the bootrom, not on the cartridge.

When this bootrom finishes scrolling, it checks value-by-value that what was drawn on the screen is the Nintendo logo. If the logo was pixel-by-pixel identical to the one in the bootrom, the game will continue to boot. If the cart doesn’t contain the Nintendo logo, the gameboy freezes. (It doesn’t even STOP, in the language of hardware user manuals and programming guides. It just loops forever.)

The ROM checks against the Nintendo logo because that logo is a trademark of Nintendo. To get the gameboy to run your game, you needed to put the actual bytes of an actual picture of the Nintendo logo in your game. And if you included the Nintendo logo in your cartridge, but weren’t officially licensed by Nintendo, they could sue you for trademark infringement.

What a clever form of copy protection and content control! Nintendo didn’t need to give you a secret key or anything; they had full control over which games got released. It’s clever and kind of icky, in a way. It’s the kind of solution you come up with if you have a huge legal department.

But the actual thing I’d like to tell you about today is the story of how someone figured out what exactly was happening.

I mean, people generally knew that this logo check was happening. If you were making a game, Nintendo told you directly. Otherwise, your game wouldn’t run! And if you were a hobbyist trying to make something that ran on a gameboy, clearly if you put in a game without the Nintendo logo it wouldn’t start.

But it was tricky to find out what that bootrom was, exactly—what code was running.

With games, they’re meant to be taken out and plugged back in, which means you can plug them into a device that will extract their data. You can come back ten minutes later and say, ah, there’s the code. That’s a 1 and that’s a 0 and so on. But this ROM is nestled inside the CPU, which is encased in resin. There was no way to access that chip’s inputs and outputs.

By 2005, this minor mystery was of interest to only a few hobbyists. The Game Boy had become the Game Boy Color and then the Game Boy Advance and then the Game Boy Advance SP and then the DS. Emulator developers had written their own bootroms that jumped straight into the game cartridge’s code.

No one was terribly interested in this.

Until a materials science undergrad at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, who goes online by the name “neviksti.”

Early that year, he got access to a scanning electron microscope, and immediately thought of using it to look at chips from video game consoles. His original goal was to look at Super Nintendo hardware, but a little while after posting about the microscope on the CherryRoms forums, someone sent him a gameboy CPU.

The resin the surrounded the CPU was still a problem. He tried a few trial runs with copy-protection chips scavenged from NES systems. Scraping off the resin with a metal file didn’t work—it was too rough, and destroyed the silicon. Physical methods wouldn’t work. How about chemical methods?

He asked a friend in the Chemistry department—could I have some strong acid? Some hydrofluoric acid to dissolve the resin around this chip?

Now, HF is an acid so corrosive that it eats through glass. It is so poisonous that, should you get it on your skin, it will dissolve your bones. His friend refused him in what were implied to be strong terms. However, this friend suggested nitric acid, and passed some over.

Nitric acid is not great either! Should you get it on your lab gloves as you’re working, your gloves will catch on fire. If you’re not wearing lab gloves (the recommended procedure at the time) it reacts with your hands, which is also unpleasant. But it’s very, very good at dissolving the resin around a CPU. If you’d like, you can watch someone distill nitric acid here.

He went outside onto the university lawn on a sunny day in May. He dropped a gameboy CPU into a sample vial filled with nitric acid and lowered the vial into a pot of boiling water. The resin in the chip reacted with the acid, and nitrogen dioxide gas billowed up into the Illinois sky.

It probably smelled awful.

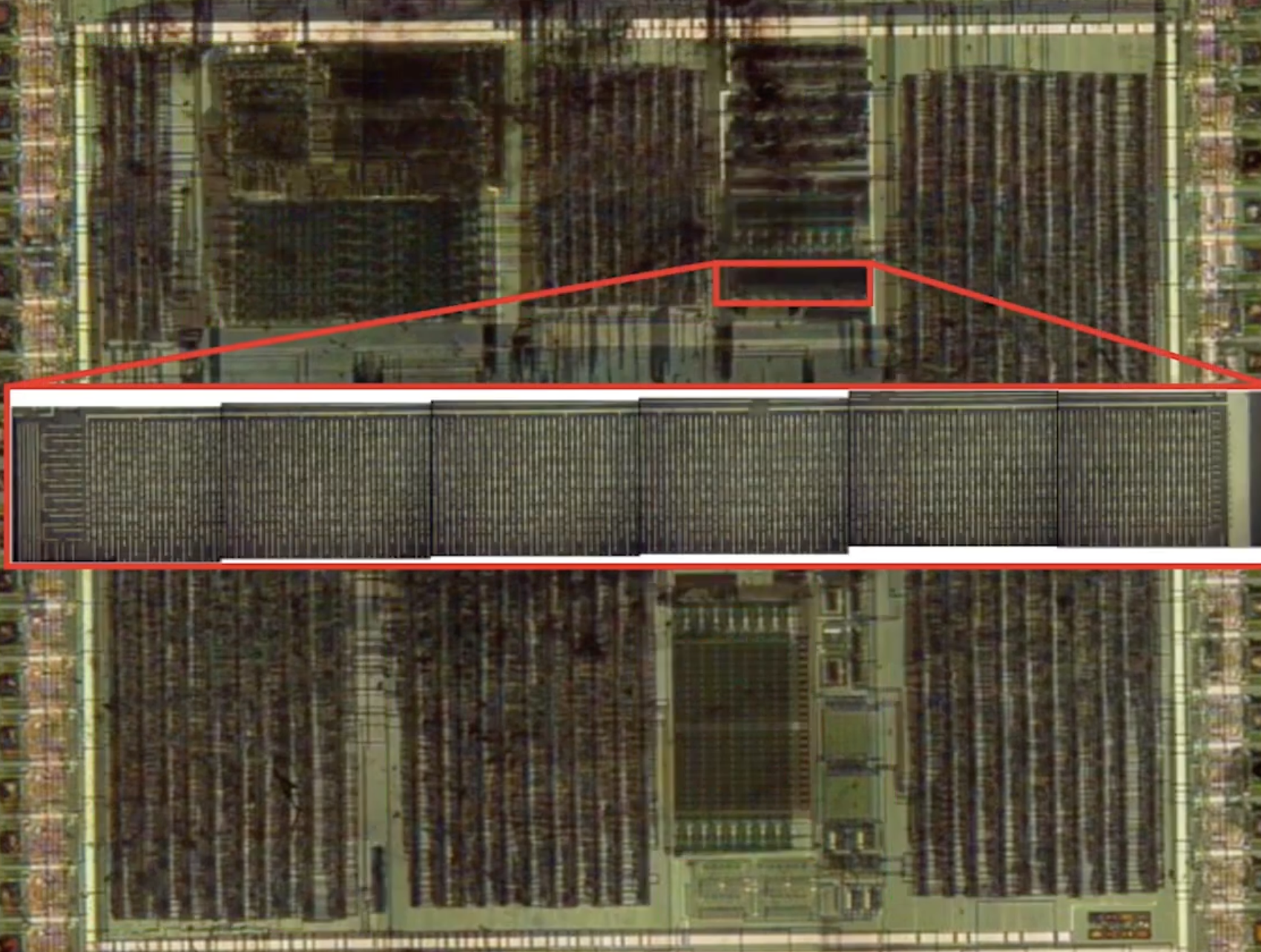

If you’d like to take a look yourself, here are neviksti’s own microscope pictures that show the decapsulated chip. You can barely see the bootrom, a tiny strip of silicon near the middle.

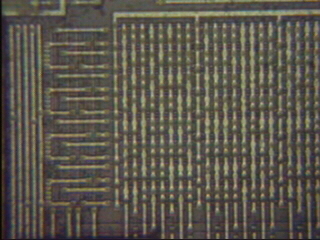

This is “masked rom,” popular in the earlier days of circuit-board computers. It takes up a lot of space, but it’s dead simple to manufacture. Each dot of solder represents a 1, and a blank space represents a 0. You can read the computer’s memory just by looking at it!

It’s read bottom to top, left to right. Can you see where the blobs start? The first sequence of bits is 01001001, and the second is 01101110.

Here, the author transcribed the entire thing. Open that in another tab, if you’d like, so you can follow along.

Now, none of these bytes are sensical Gameboy CPU instructions. The next thing to do is determine how the CPU reads this memory. It could be from left to right, or in columns, or interleaved. The author never wrote how he figured this part out — he only noted, with an engineer’s knack for understatement, that it should have taken him much longer than it did.

The layout escaped me for days, so I wrote to Luna. She got it in a few hours:

I think I’ve figured out the layout, it’s really weirdly interleaved. The first byte of the rom is spread out across the last digit of the first row of alternate blocks of the decap, and then subsequent bytes are in the bits to the left, then the next rows, and then the other alternate blocks.

Ok! Following Luna’s instructions, we read a bit from the top-right corner of the first block: a 0. Then skip a block, and read the top-right: a 0. Going down every other block, we get: 00110001. That’s a valid Gameboy Z80 instruction! It’s instruction 0x31, which is LD SP,d16: “load stack pointer with two bytes.”

Move one digit to the left, and repeat: 11111110. Again one digit to the left: 11111111. That’s the value for the stack pointer — 0xFFFE, for the gameboy’s little-endian CPU. There, the stack is initialized! If you’d like to read the rest, you can find it here.

“Apart from amazement,” reads a page on a wiki for modern-day gameboy programmers, “the dumping of the DMG bootrom led to the inclusion of a feature to emulate the bootstrap ROM in the emulators KiGB and BGB.”

You can learn a lot about a computer from looking at it.

In these days of NAND-gate based ROM, the community of people who investigate these kind of things has decided it’s too difficult and confusing to look at circuits with a microscope, and have moved on to different techniques. One is called “clock glitching”, which is a wonderful pair of words, and maybe a topic for a different letter.

Some hackers and researchers still think it’s a good idea to look at computers very carefully. They might be right.

The original CherryRoms thread about this decapsulation contains some wonderful commentary, like someone asking if they should buy a scanning electron microscope off eBay.

This has been About Computers. Thank you so much for reading.