About Telegraphs

Here’s the thing about telegraphs:

Sometimes, telegraph operators had bad days. This was usually for mundane reasons. A telegraph pole down. Electrical failures: too much current, burnt wire insulation, or maybe over-curious sheep near the ground return.

On September 2nd, 1859, many telegraph operators had a worse-than-usual day.

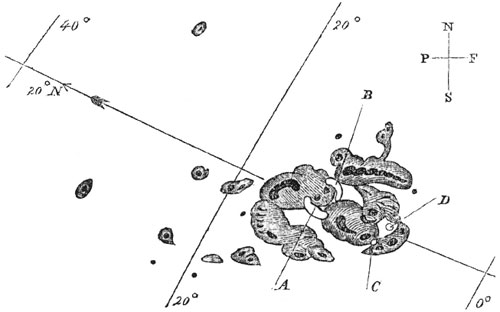

It looked like this:

That is how the astronomer Richard Carrington drew a truly immense solar storm. It was the kind of thing that would kill all of the electric grids, everywhere, should it hit today.

The solar storm of 1859 appeared as an aurora of remarkable intensity in Queensland, Australia. (Please note that Queensland is quite close to the equator, and is not at all the kind of place an aurora should be visible.) The sighting showed in the Moreton Bay Courier, a Brisbane newspaper, next to news about an overturned oxcart (“LAMENTABLE ACCIDENT”) and a butcher’s recent purchase (“FAT BULLOCK AND SHEEP”). People gathered in front of Mr. Sparke’s butcher’s and admired the quality of meat and the size of the steer. They talked about what they had seen in the sky that previous Friday evening.

(By the way, there was a solar storm last Tuesday. A much, much smaller one. Sadly, it was too small for an aurora to appear south of, say, Edmonton).

I am spending this time telling you stories about telegraphs because computers have just gotten stuck with all of this.

The BSD 4.4 kernel – and later versions, including the Darwin kernel running in my Macbook – contains a simple emulator for a telegraph-printer. It is about 80 lines of C, the meat of it at least. It takes care of things like “when a letter is typed, advance the typewriter carriage a little”, and “when there’s a new line, move the paper up (a ’line feed’) and return the carriage”.

If it wasn’t clear, that is what the terminal is.

That interface–signals to a typewriter over a telegraph wire–was established in the 1910s and 20s and 30s, standardized in the 1980s under ANSI, and just hasn’t been touched since. There was no need, I suppose.

The aurora, in the small hours of that September’s morning, was so bright that mine workers in the Rocky mountains rolled out of their blankets. They got partway through cooking breakfast before someone looked at the time and noticed that it definitely wasn’t dawn.

The telegraphs couldn’t handle it. A few of them just burst into flame. Some threw sparks, shocking their operators or igniting the papers around them. Luckier operators noticed the power surge and cut off their batteries.

Operators in Boston, Mass. and Portland, Maine quickly corresponded to advise each other to disconnect their batteries, then continued their daily work with the auroral current. I am astonished by this, because it implies a working knowledge of electricity that is so, so much better than mine. (I would have said something astonished, then tried to douse the fires)

The programming language Erlang was written to program telephone exchanges, and it has taken over that job completely. Telegraph and switchboard operators are long gone. I do hope that someday that an Erlang program catches itself on fire, but until then it will remain a small cruelty of automation. We use Erlang to write databases and distributed systems and chat apps and, in one weird case, 3D art software. Its manuals and libraries still use the language of telecommunication.

You can find sections in old computer manuals where letters that needed to be printed in bold type are written several times in a row, lllliiiikkkkeeee tttthhhhiiiisss, because with a teleprinter you made things bold by overstriking them. The backspace-codes, in this case, have been lost in some format transition.

This has been About Computers. Thank you so much for reading.